A study of new technology reveals a huge volume of liquid water exists, under the Martian surface, big enough to give the whole planet an ocean one mile deep. are behind the groundbreaking finding that is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

T his finding continues to fuel the discussion about a few questions in life as such pertaining to the Red Planet that nurtures the needs of feeding extraterrestrial organisms.

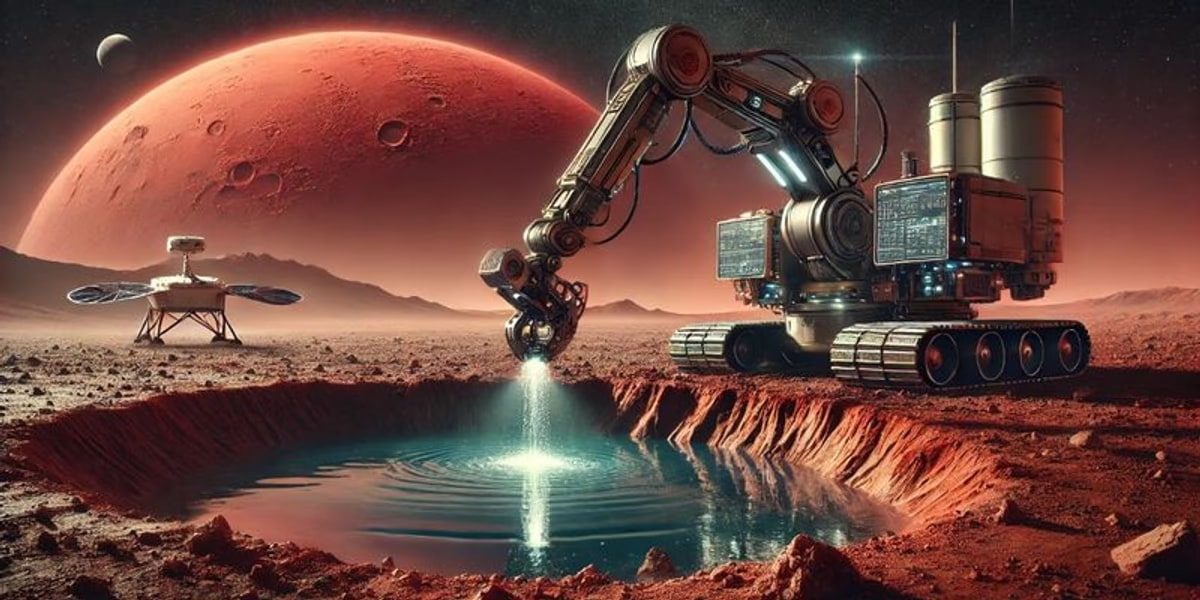

The researchers relied on seismic data recorded by NASA's InSight lander in the form of quakes, volcanic activity, and meteor impacts on a secret water reservoir that hoards in Mars. They could find water trapped in tiny fractures and pores some 11.5-20 kilometers beneath the Martian surface, using similar rock physics models that locate underground aquifers and oil fields on Earth. At present, these newly identified reserves are beyond reach of existing technology; however, this reserve replete with information in the history of Mars pertaining to habitability.

Michael Manga, a Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science and one of the study's authors, believes such deep subsurface environments on Mars could harbor life. "We haven't found any evidence for life on Mars, but at least we have identified a place that should, in principle, be able to sustain life," says Manga. This perspective would mean that Mars could still have locations suited to hosting microbial life even though, on average, it is an arid planet.

Although Mars is a desert planet at present, vast quantities of water were once present on the planet. The most important geological features that testify to the presence of liquid water on the surface very long ago on Mars are ancient river valleys and lake bottoms. If this underground reservoir has been discovered, then it follows that a significant fraction of this water must have been lost to the planet's crust rather than being totally lost in space. This completely changes our view of Mars's water past and, more importantly, its evolution, revealing a much more complex history than previously supposed.

The research also identifies several uncertainties. Examining the past water resources of a planet involves, on one level, an immense number of assumptions, to say the least, that Martian rock physics was the same as Earth rock physics. Thus, whereas the results derived so far suggest a saturated mid-crust, the volume and exact depth of this store remain highly speculative. That again reflects more general problems in planetary science and the problem of mapping such inaccessible resources with any real accuracy.

These results are important, said Vashan Wright, a coauthor of the research paper and a professor at UC San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography. "Understanding the Martian water cycle is central to understanding the evolution of the planet, its surface, and its climate," said Wright. Knowing where that water resides, how much exists serves as the first stepping stones into deciphering the intricate geological and climatic history of Mars.

Put another way, think of the Russian Kola Superdeep Borehole, the deepest hole ever dug by humans on Earth, reaching a depth of 12,262 meters. That's shallow, however, compared with end estimates for the water reservoir on Mars, and so problems presented by deep drilling are of prime importance there. In this respect, an aggressive aim of going beyond this to be mined further is left for the future, indicating deficits from current technology.

It opens new avenues to better understand the potential Martians hold in hosting life. At this current level of technology, any future attempts to get to such water would be futile. Such research adds key insights to the history of water on Mars and its habitability. Such discoveries might thus help scientists as they continue with the exploration of Mars in future missions and once more deepen our knowledge of the mysterious past of the Red Planet.

.jpeg)